October 30 , 2018.

Peru , Sabancaya :

An average of 30 Explosions / day was recorded. The activity associated with the movement of fluids (long period type events) continues to predominate. Earthquakes associated with the rise of magma (hybrid types) remain very few and low energy.

The columns of gas and eruptive ash reached a maximum height of about 3,400 m above the crater. The dispersion of these materials occurred within a radius of about 40 km, mainly in the Southeast, East, Northeast directions.

On October 27, the volcanic gas (SO2) flow recorded a peak value of 2671 tonnes / day, considered a significant value.

The deformation of the volcano surface showed significant variations.

Five thermal anomalies were recorded according to the MIROVA system, with values between 5 and 15 MW VRP (Radiated Volcano Energy).

In general, eruptive activity maintains moderate levels. No significant changes are expected in the coming days.

Source : IGP

Photo : inconnu

La Réunion , Piton de la Fournaise :

Activity Bulletin from Monday, October 29, 2018 at 16:30 (local time).

The eruption started on September 15th at 4:25 am local time continues. The intensity of the volcanic tremor (indicator of eruptive intensity at the surface) remains relatively stable at very low values for a few days (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of the RSAM (indicator of the volcanic tremor and the intensity of the eruption) between 04h00 (00h UTC) on September 15th and 16h22 (12h22 UTC) on October 29th on the seismic station FOR, located near the crater Château Fort (2000 m altitude on the southeast flank of the terminal cone) (© OVPF / IPGP).

– No volcano-tectonic earthquake was recorded during the day of October 28, nor during the current day.

– Inflation (swelling) of the building is always recorded. This inflation reflects the pressurization of a localized source beneath the summit craters (Bory-Dolomieu) at a depth of 1-1.5 km, related to the recharge of the superficial reservoir by deeper magma.

– SO2 emissions at the eruptive vent are low (near or below the detection limit).

– CO2 emissions from the soil at the volcano deposit remain low.

– The surface flow rates could not be estimated today because of lava flows that are too weak at the surface and because of the cloud cover on the south of the enclosure.

Alert level: Alert 2-2 – Eruption in the Enclos.

Source : OVPF http://www.ipgp.fr/fr/ovpf/bulletin-dactivite-lundi-29-octobre-2018-a-16h30-heure-locale

Photo : IPR https://www.facebook.com/ipreunion/photos/a.999761746714742/2152363651454540/?type=3&theater

Philippines , Mayon :

MAYON VOLCANO BULLETIN 30 October 2018 08:00 A.M.

Mayon Volcano’s seismic monitoring network did not detect any volcanic earthquake during the past 24 hours. Moderate emission of white steam-laden plumes that drifted east-northeast and northeast was observed. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) emission was measured at an average of 806 tonnes/day on 24 October 2018. Precise leveling data obtained on 30 August to 03 September 2018 indicate significant short-term deflation of the edifice relative to 17-24 July 2018. However, the volcano generally remains inflated relative to 2010 baselines. Electronic tilt data further show pronounced inflation of the mid-slopes beginning 25 June 2018, possibly due to aseismic magma intrusion deep beneath the edifice.

Alert Level 2 currently prevails over Mayon Volcano. This means that Mayon is at a moderate level of unrest. DOST-PHIVOLCS reminds the public that sudden explosions, lava collapses, pyroclastic density currents or PDCs and ashfall can still occur and threaten areas in the upper to middle slopes of Mayon. DOST-PHIVOLCS recommends that entry into the six kilometer-radius Permanent Danger Zone or PDZ and a precautionary seven kilometer-radius Extended Danger Zone or EDZ in the south-southwest to east-northeast sector, stretching from Anoling, Camalig to Sta. Misericordia, Sto. Domingo must be strictly prohibited. People residing close to these danger areas are also advised to observe precautions associated with rockfalls, PDCs and ashfall. Civil aviation authorities must advise pilots to avoid flying close to the volcano’s summit as airborne ash and ballistic fragments from sudden explosions and PDCs may pose hazards to aircrafts.

Source : Phivolcs

Photo : Business Travel. https://www.businesstravel.fr

Italy , Sicily , Etna :

Once upon a time … the central crater of Etna. Dr. Boris Behncke.

Figure 1 – Aerial view of the central crater in its « classical » form (circa 1920). On the left edge of the image, you can see the gas plume emitted by the northeast crater, born in the spring of 1911. Based on an old postcard.

How often do visitors to Mount Etna ask if it is possible to see « the crater », that is to say the famous central crater, great mouth of the Sicilian volcano! Even among the guides of the volcano, we often speak of the central crater, when in fact we are referring to one of the four main craters of the summit, the one called « Voragine ». The old great mouth, precisely the central crater, whose truncated cone has dominated the profile of Etna for centuries, has not existed for half a century, since it has been filled with the product of its eruptions in the first half of the sixties.

According to the analysis of historical sources for many centuries, the crater at the top of Etna would have always been unique, even if there had been no eruptions – the so-called « subterminal » eruptions » such as the one from 1869 – originated from eruptive mouths slightly lower than the Central Crater.There is no evidence that, at least over the past 500 years and perhaps several millennia, a complex of cones and craters like this one already exist in the summit region.The descriptions provided by those who climbed and reached the top of Mount Etna always refer to one and the same big crater, sometimes with only one internal mouth, sometimes with two This crater was characterized by a more or less continuous activity between a lateral eruption and another, and rare paroxysmal episodes with fountains and lava flows, formation of columns of pyroclastic material, even in 1787, 1800 and 1863., 1899 and in 1910.

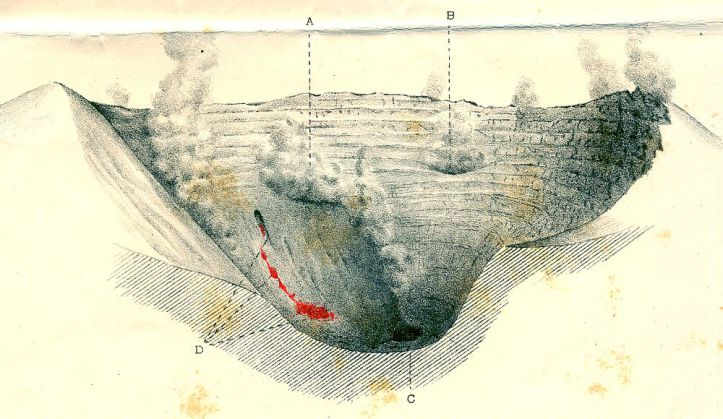

Figure 2 – Drawing of the central crater, with a small intracratic lava flow, in 1893, one year after the great eruption of 1892 that had built the Silvestri Mountains on the south side. Drawing by Annibale Riccò.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the central crater had a diameter of almost half a kilometer and a depth of several hundred meters (Figures 1 and 2). During the second decade of the 20th century, a lively and almost continuous intra-crater activity began to fill the crater, forming a slag cone at the base of its northeast wall. After a period of subsidence and the collapse of the central part of the crater floor, a new period of intra-crater activity began in 1939. This led to the growth of slag cones with the emission of lava flows in the central crater (Figure 3), culminating in two paroxysmal episodes in 1940 and a third in 1942, which almost completely filled the Great Depression of the crater (Figure 4).

Figure 3 – Double cone of slag and intra-crateric lava flow in the northeastern part of the central crater, 1940. Based on an old postcard.

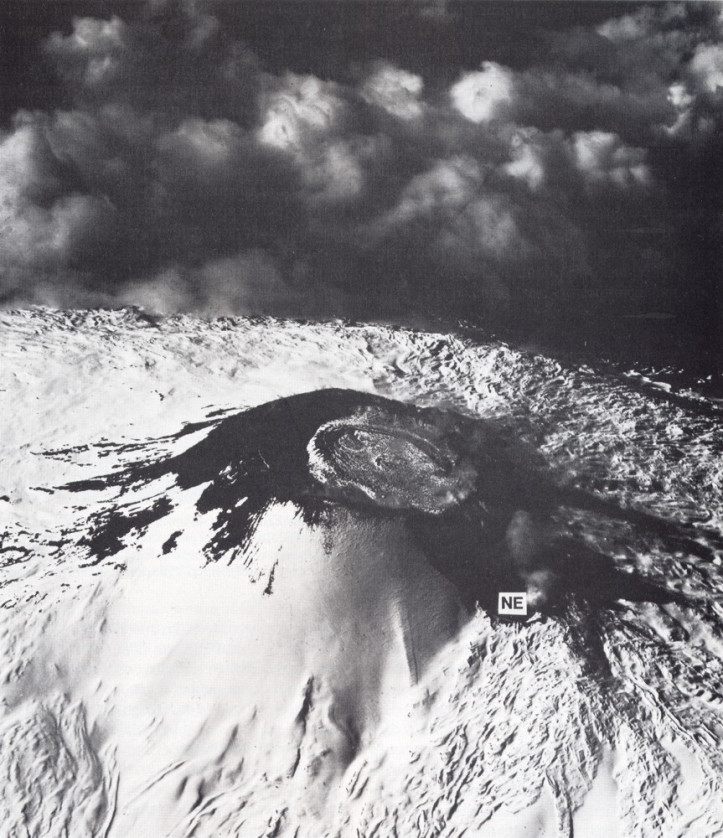

Figure 4 – Aerial view of the central crater in 1943, taken by Allied forces during the landing period in Sicily. The crater is almost completely filled by an intra-crateric lava flow emitted during the paroxysmal episode of June 1942. In the foreground, the very small crater of the northeast, which was still very tiny. Photo published in the book « Mount Etna – The Anatomy of a Volcano » by Chester et al. (1985) (see bibliography at the end of the article).

During the last twenty years of its existence, the central crater has undergone significant changes. In October 1945, a « well » was formed in the north-eastern part of the internal lava platform, called « Voragine » (or « Voragine Grande »). In 1949, an eruptive fault opened, oriented North-South. After having completely crossed the western part of the central crater, it extended further on the southern and northern flanks of the central cone (Figure 5).

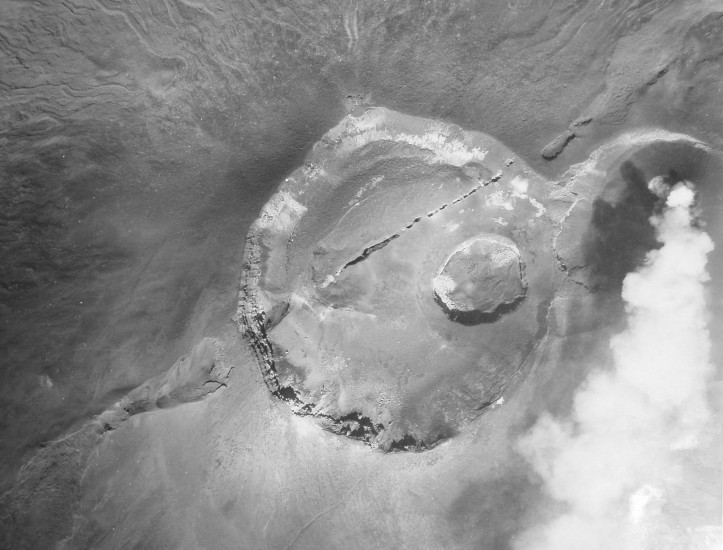

Figure 5 – Vertical aerial view of the central crater after the eruption of December 1949, which opened a spectacular eruptive fracture across the western crater and on the southern (left) and northern flanks. The Voragine crater, opened in the fall of 1945, was not affected by this eruption. From the personal collection of Santo Scalia.

Inside the central crater, other eruptions, with paroxysmal episodes, occurred in 1955 and 1956. In 1956, the paroxysm occurred from eruptive chimneys placed in the central-south part of the crater where a pyroclastic cone was formed several tens of meters high. During the 1956 eruption, lava flows from the central crater were also observed for the first time, then headed north toward the Northeast Crater. In the summer of 1960 (17 and 20 July and then 5 August), Voragine again produced very violent paroxysmal episodes. In May 1961, a brief eruption caused further lava flow from the central crater to the north and west (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Aerial view of Central Crater and Northeast Crater (background left) in 1961, looking northeast. South of the central crater (in the foreground) is a large pyroclastic cone formed during the paroxysmal eruptions of 1956 (and perhaps also in 1961). Farther back, the Voragine emits a gas plume (slightly retouched) and is surrounded by a lava field formed during the paroxysmal activity of May 1961. During this activity, a lava flow occurred towards the North-North-West (left). At the bottom right, you can see the southernmost part of the 1949 eruptive fracture on the side of the central cone. From the private collection of Santa Scalia.

But it was the February-July 1964 eruption that so upset the central crater area that it disappeared forever. During this event, several eruptive mouths were active inside and outside the central crater. The first phase of the eruption, from 1 to 20 February, was mainly limited to Voragine, from which a lava flow was emitted towards the Northeast crater and an eruptive fracture opened on the eastern flank of the central cone. . The second phase lasted from April 7 to July 5, with a long sequence of brief paroxysmal episodes and a slightly longer eruption episode (May 7-19). In addition to Voragine, which was probably the source of the most intense activity and allowed the growth of a large pyroclastic cone, other mouths were activated along a small north-south trending eruptive fracture. the western part of the central crater. Another eruptive mouth, known as the « crater of 1964 », opened in the southern part of the Central crater, forming a pyroclastic cone about ten meters high. Numerous eruptive episodes from April to July 1964 resulted in lava overflows, first to the Northeast Crater and to the West, then to the North, Southwest and Southeast. Figure 7 shows one of the outflows, in the South, in mid-May 1964.

Figure 7 – Lava overflow on the southern flank of the Central cone and strong strombolian activity at the « crater of 1964 » in mid-May 1964. Photo published by « Epoca » on July 14, 1964.

After the eruption of 1964, what was once the huge central crater left only a few remains of its edge in the West and Southeast (the latter is still recognizable today). Four years later, the Bocca Nuova opened, which is now the largest of the four craters of the summit. Several times over the last few years, it seemed that Etna was trying to reconstruct the original central crater by uniting Voragine and Bocca Nuova into a crater depression. However, the 2015-2016 Voragine and 2018 Bocca Nuova activities showed that they were two close but surprisingly distinct crater structures, each with its own feed pipe and eruptive style. .

Finally, the widespread habit among Etna’s guides and other connoisseurs of calling the crater of Voragine also by the word « Central crater » is not totally misleading. Although this crater occupies only about a third of the surface of the old central crater, it is located exactly in the center of the crater complex at the top of Mount Etna, and so is above what is considered the main supply pipe of the volcano. Of the craters at the top of Etna, Voragine erupts less often, but some of its breakthrough episodes are among the most violent eruptions of Etna, as in 1998-1999 and in 2015.

Source : INGV Vulcani , Dr Boris Behncke .

Read the bibliography and the original article : https://ingvvulcani.wordpress.com/2018/10/29/cera-una-volta-il-cratere-centrale-delletna/